Brahms: Violin Concerto

Lakeview Orchestra will perform Brahms’ Violin Concerto on Tuesday, October 2nd at 7:30PM at the Athenaeum Theatre.

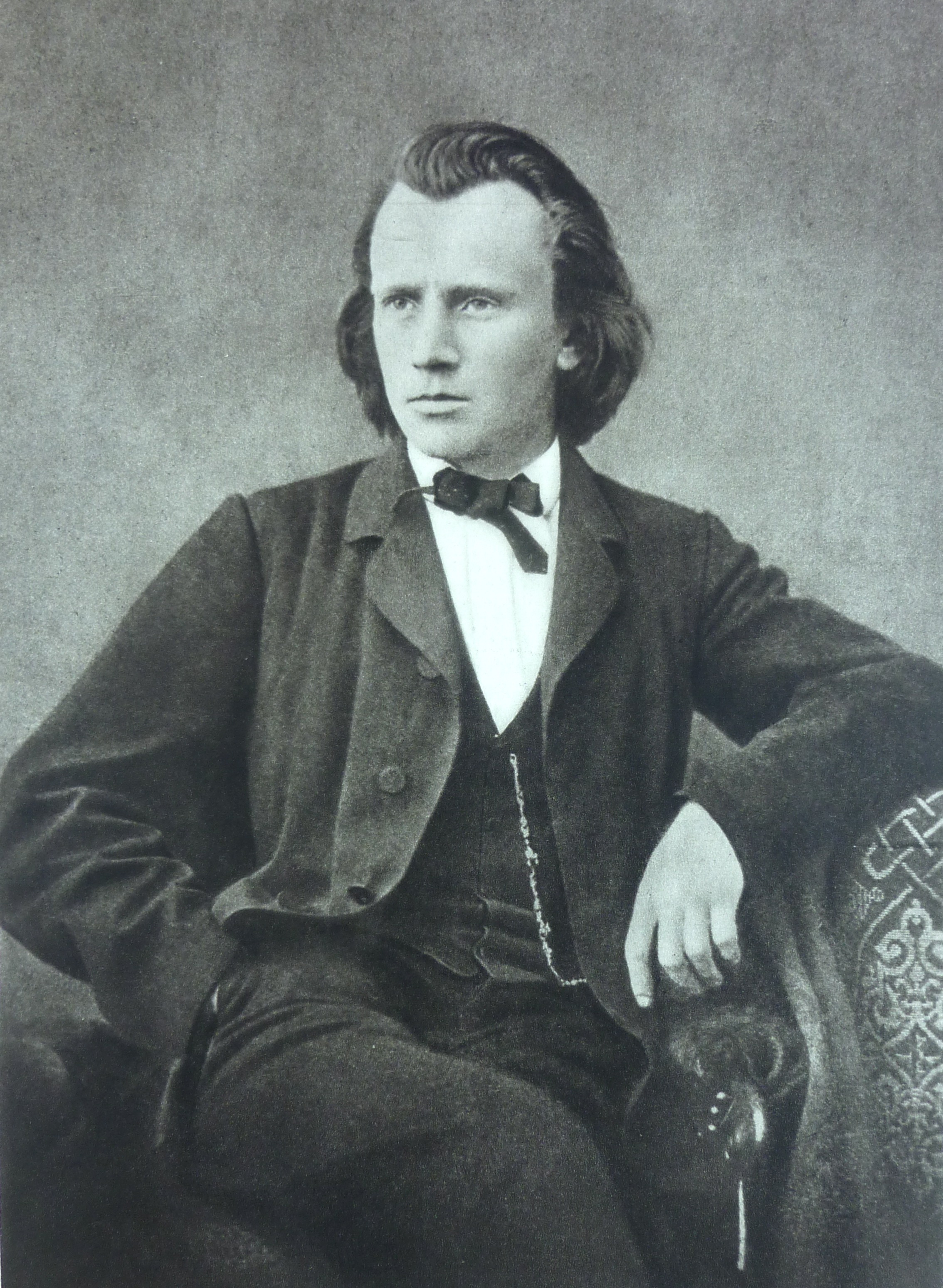

Johannes Brahms was a passionate and problematic man whose personality might best be described as the good, the bad, and the ugly. The product of a working class family, Brahms was an inveterate rooter for the underdog. Rich and famous in his lifetime, he gave his money away by the handful. He was a friend and benefactor to young

musicians and composers, including Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904).

A man of extraordinary wit, and something of a practical joker, Brahms never felt obliged to fit the expected societal mold as a world-renowned composer. He adored children and generally preferred their company to that of adults. At gatherings he could often be found down on his hands and knees playing with the kids. Remaining something of a child himself, even as an adult Brahms still loved to play with his toy soldiers.

But with Brahms, one had to take the good with the bad. Brahms’ great friend, the Hungarian born violinist and conductor Joseph Joachim (1831-1907), to whom Brahms’ violin concerto is dedicated, famously said that, “Sitting next to Brahms is like sitting next to a barrel of gunpowder!” Despite the fact that the adult Brahms barely topped out at five feet tall, those who knew him tiptoed around him as one would a growling pit bull. He had zero tolerance for the pretentious attitudes of the concert world in which he lived and worked, and he was known to mercilessly demolish fans, particularly affluent benefactors, who were foolish enough to approach him and share their impoverished views on the state of modern classical music.

Famous for his rudeness, friends recalled a soirée Brahms attended in Vienna at which he seemed to affront every critic, patron, and concertgoer who approached him, some who innocently suggested what they wanted him to write next and even change about a work already published. Eventually disgusted with the pomposity and snobbery of the party’s constituents, Brahms marched to the door, proclaimed he was leaving and howled, “If there’s anyone here whom I haven’t insulted, I APOLOGIZE!!”

Despite what appeared to be Brahms’ bloviating as a notable composer, the reality is Brahms was a truly sensitive man who was hardest on himself and most critical of his own work. He once remarked, “It’s not hard to compose, but it’s wonderfully hard to let the superfluous notes fall under the table.” By his own admission, Brahms let countless works “fall under the table”: Some 20 string quartets, manuscripts, sketches, papers, and musical memorabilia were burned in the furnace. Even as late as 1880, he requested his friend Elise Giesemann destroy the choral works of his she had in her possession. He believed his music was unreservedly inferior to that of his idols Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. Brahms was terrified by the prospect of posterity and wanted only his very best works to survive. He believed the scrutiny to which his unpublished works and sketches would be subjected could only diminish his reputation as a composer. Understood this way, Brahms’ thorniness was – as is so often the case with big personalities – a cover for his own fear.

Brahms was born on May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, the largest port city in Germany. Brahms’ father, Johann Jakob, was a mediocre violinist who lived and eked out a living in the waterfront dives and brothels of Hamburg’s red light district, Gängeviertel, locally known as the “Adulterer’s Walk” for its active sex trade. This occupation was forced upon him after a short-lived career as an entrepreneur with a penchant for bad financial investments. These waterfront dives, called Animierlokale (roughly translates as “stimulation pubs”), were combination restaurants, saloons, dance halls, and brothels. The euphemistically called “singing girls” who worked these pubs were combination waitresses, bar maids, dancers, and prostitutes. A musician who played in such a joint was compensated a small stipend and all he could drink. At 12 years of age, Brahms’ father hired out little Johannes to play the piano in the same waterfront dives as he played – an incredibly idiotic and ill responsible parental move.

Later in his life Brahms told Clara Schumann that he “saw things and received impressions that left a deep shadow on my mind.” Musicologist Jan Swafford writes further what Brahms experienced: “Johannes was surrounded by the stench of beer and unwashed sailors and bad food, the den of rough laughter, and drunkenness and raving obscenity. He had to accompany the songs, he had to look sometimes at the drunken sailors fondling the half naked singing girls, and he had to participate sometimes too. Between dances the women would sit the prepubescent Brahms on their laps and pour beer in him and pull down his pants and hand him around to be played with to general hilarity of onlookers. There may have been worse from the sailors as Johannes was as fair and as pretty as a girl.” It doesn’t take a clinical psychologist to figure out where and when Brahms’ lifelong phobia of intimacy and preference for prostitutes and married women began. By the time he was 14 years old, Brahms’ schizoid life – gifted musician and hard working student by day, saloon pianist by night – had taken its toll. He suffered from migraine headaches and was anemic, underweight, under rested, and emotionally overwrought. His parents finally figured out that sending him out at night to play was unadvisable, but to Brahms’ psyche, the damage was done.

Brahms’ parents, still eager to capitalize on Johannes’ talents as a musician, tried to book more reputable gigs for the boy. Brahms composed and played his own piano works as well as compositions from the masters in little concert halls around northern Germany. His remarkable talent as a pianist and composer was eventually brought to the attention of world-renown pianist and teacher Eduard Marxsen (1806-1887). Marxsen was stunned by Brahms and took him as a student four times a week free of charge. It was Marxsen who grounded Brahms in the music of Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, and it was Marxsen whose confidence and support allowed Brahms to blossom as a composer. When Felix Mendelssohn died Marxsen said, “A great master of the musical arts has gone hence, but an even greater one will bloom for us in Brahms.”

Through Marxsen Brahms was introduced to all manner of the who’s who of the world of classical music. Brahms’ musical connections, musical understanding, and musical development and status were now far removed from the shady seedy stimulation pubs that launched his musical career. By the age of 20 Brahms was introduced to the eminent violinist Joseph Joachim. Joachim’s success and talent as a violinist cannot be understated. Appointed professor of violin at the Leipzig Conservatory at 17, concertmaster at the Weimar court orchestra at 19, and concertmaster and violin soloist of the Hanover Court Orchestra at 20, the high-end credentialed Joachim found somewhat of a kindred spirit in Brahms. The two began a friendship based in mutual respect and fondness that lasted the remainder of their lives. Recalled half a century later after first hearing Brahms perform a work he wrote for piano, Joachim wrote, “Never in the course of my artists life had I been more completely overwhelmed.” What Joachim heard was piano music with the expressive power of Beethoven, compositional discipline of Bach, and the melodic grace of Mozart.

In 1877, 24 years after Brahms and Joachim met, Brahms decided to start writing a violin concerto. It was the world’s biggest no-brainer since this side of “Don’t eat yellow snow” that the concerto was going to be for Joachim. The work premiered on January 1, 1879, with Joachim as the soloist and Brahms as the conductor. The unusual format and style of the concerto elicited harsh comments from critics at its premiere. Perhaps the most famous is that of conductor Hans von Bülow, who remarked that Brahms had composed a concerto against the violin, whereupon violinist Bronislaw Huberman responded, “It is a concerto for violin against the orchestra – and the violin wins!”

The Allegro non troppo is a true collaboration between orchestra and soloist. The slow orchestral exposition contains the seeds for most of the subsequent themes presented in the movement. The soloist eventually enters playing a ravishing, shimmering, extended, and highly embellished version of the orchestral introduction theme and in doing so transforms it into something a thousand times more lyric and expressively more complex than what it was in the orchestral exposition. This movement combines Brahms’ laser-like intensity with gentler passages, ending with a cadenza, a written-out ornamental passage played by the solo violinist allowing virtuosic display. There are at least 21 cadenzas written for this concerto. Tonight you will hear an exceptionally superb cadenza written by the Austrian-born violinist Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962).

Although Brahms, in his usual self-deprecating way, described the second movement as “a poor Adagio,” for some listeners it is the most beloved of the three. A solo oboe presents the main theme, one of immutable tranquility. In the words of a French critic, “Le hautbois propose, le violon dispose” (The oboe proposes, the violin disposes). The violinist echoes and elaborates on the theme, tracing airy arabesques of sound.

In the finale, the Allegro giocoso, Brahms gives us drama and fire. Written as a marvelous rondo, the main theme showcases the soloist’s extraordinary facility, but as with the preceding music, the violin and the orchestra blend their combined abilities to create a sound full of irrepressible joy, concluding with a gypsy-like jingling, jangling march.

Lakeview Orchestra will perform Brahms' Violin Concerto on October 2nd, 2018: Learn More or Get Tickets

Program notes by Luke Smith.